Words and Music through Love and Life

Part 4 of Series

Besides my other brothers, Mentz has influenced my penchant for music, even as he has wonderfully sung and danced his way through love and life.

Though he was not much of a child performer himself, he later has taken to the family program stage like a natural, class act as he has done to presiding matters for (the rest of) our family.

Years ago, I called him to be the Speaker of the House—i.e. our household—because he has hosted and also literally presided our family (gatherings) since 1996. One with a quiet and unassuming disposition, Mentz has always taken to the microphone as if it’s public performance.

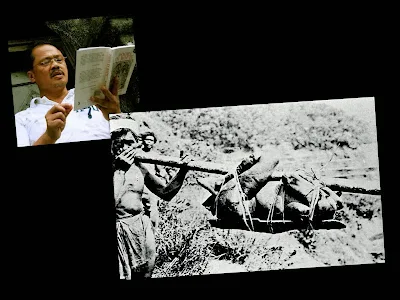

Through the years, Mentz has been trained to become a very good public performer. At the Ateneo high school, he led the Citizens Army Training (CAT) Unit’s Alpha Company, a well-respected group finely chosen to parade to give glory to Ina (Our Lady of Peñafrancia) in September in Naga City.

Then in college, Mentz did not only win a Rotary-sponsored oratorical contest; he also served as junior representative in the college student council. And before graduating in 1994, he won a graduate scholarship at the University of the Philippines where he would later obtain his graduate degree. And because he went to Manila all ahead of us, I always thought he has been exposed to the world way before his time.

In the late 80s and early 90s when he was making the transition from being a high school achiever to a college heartthrob at the Ateneo, Mentz played Kenny Rogers and Tom Jones on Manoy’s cassette tape. Sweet sister Nene and I would always joke at how he covered a singer's song better than the singer himself.

In those days, he deftly worded the first lines of “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” as he cleverly impersonated the speaker in “The Gambler”—sounding more Kenny Rogers than the bearded country singer himself: "on a warm summer's evenin, on a train bound for nowhere..." For us, his siblings, no one did it better than Mentz. Not even Kenny Rogers.

Perhaps because I listened to him passionately crooning away Tom Jones’ “Without Love” that I also heard the lyrics of that song after the overnight vigil of the Knights of the Altar inside Room 311 of Santos Hall. I thought I was dreaming but it was in fact Mentz’s tape playing on my classmate Alfredo Asence’s cassette player. Truth be told, I could not do away with the passionate singing that I had carted away Mentz’s tape for that one sleepover in the Ateneo campus.

In 1995, Mentz brought Enya’s “The Celts” and Nina Simone’s collection to our new household in Mayon Avenue. He bought these tapes to fill in the new Sony component secured from Mama’s retirement funds. Most songs of these women sounded morbid but I loved them. Because I so much liked the voice that came and went in Enya’s “Boadicea,” I played it the whole day on my Walkman (which Mentz kindly lent to me) while writing my thesis on F. Sionil Jose’s Rosales saga.

In early January of 1996, Mother would pass away.

When I played Nina Simone’s “Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair” one night during mother’s wake, one of my brothers asked me to turn it off. Perhaps it was too much for him to take. That black woman’s voice was too much to bear. But away from people, listening to these women’s songs did not only help me finish my paper; it also helped me grieve.

Among others, Mentz adored Paul Simon’s “Graceland.” Because this was the time before Google could give all the lyrics of all songs in the world, Mentz knew the words to the song by listening to cousin Maida’s tape many times through the day. While every piece in the collection is a gem, “Homeless” struck a chord in me that years later, I would use it to motivate my high school juniors to learn about African culture and literature. Talk of how the South African Joseph Shabalala's soulful voice struck a (spinal) chord in both of us.

Years later, when we were all working in Manila, I heard him singing Annie Lennox’s “Why” and miming Jaya singing “Laging Naroon Ka.” At the time, I could only surmise that he was humming away his true love and affection which he found with his beloved Amelia, a barangay captain’s daughter whom he married in 2001.

With my sister Nene, the household of Mentz and Amy in Barangay San Vicente in Diliman would become our refuge in the big city. Though Nene and I worked and lived separately from them, it was where we gathered in the evening as a family. Even as Mentz and Amy gradually built their own family, their growing household has become our own family. Through years, it has not only become the fulcrum of our solidarity; it has also become the core of our own sensibility.

Many times, I would be told how Amy and Mentz would go gaga over live musical performances by their favourite local and foreign singers. Once they told me how they enjoyed the concert of Michael Bolton, whom the couple both loved. I would later learn that Amy had a very good collection of Bolton’s albums from “Soul Provider” to the greatest hits collection. I wouldn’t wonder about it even as I have always liked the white man’s soulful rendition of Roy Orbison’s “A Love So Beautiful” since the first time I heard it. (But I think I wouldn’t trade off the Roy Orbison original.)

Years have gone by fast, and three children have come as blessings to Mentz and Amy. Once I heard him singing with his firstborn Ymanuel Clemence singing Creed’s “With Arms Wide Open,” indeed their anthem to themselves. Yman, now a graduating high school senior, has likewise taken to performing arts as a guitarist and an avid singer of alternative rock and pop. Mentz’s firstborn is one soul conceived by his father’s love for lyrics and heartfelt melodies and his mother’s love for Michael Bolton and a host of many other soulful sensibilities.

With Yman, and now Yzaak and Yzabelle, their vivo grade-schoolers (like the rest of today’s youth who can hardly wait to grow up) singing the words of Daft Punk and Pharell Williams from the viral downloads on YouTube, this tradition of song and sense and soul is subtly being passed on, with each of us now and then singing our own ways through joy, through love and through life.