Words and Music through Love and Life

Part 2 of Series

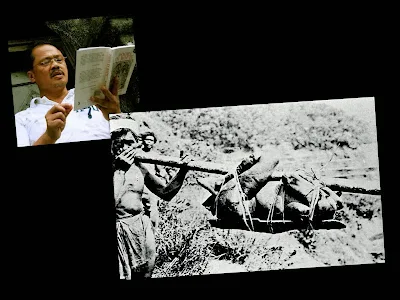

Manoy Awel, our eldest brother, has had the biggest influence in each of us, his younger siblings.

While brothers Ano and Alex strutted their way to get us equally break-dancing to Michael Jackson and his local copycats in the 1980s, Manoy’s influence in the rest of us, his siblings, is indispensable. Being the eldest, Manoy held the “official” possession of Mother’s pono (turntable) like the two Stone Tablets, where the songs being played later became the anthems among the siblings.

On this portable vinyl record player, every one of us came to love the acoustic Trio Los Panchos, Mother’s favorite whose pieces did not sound different from her aunt, Lola Charing’s La Tumba number which she would sing during family reunions.

In those days, Manoy would play Yoyoy Villame’s rpms alternately with (Tarzan at) Baby Jane’s orange-labeled “Ang Mabait Na Bata.” But it was the chorus from Neoton Familia’s “Santa Maria” which registered in my memory, one which chased me up to my high school years.

Manoy’s pono music would last for a while until the time when there would be no way to fix it anymore. A story has been repeatedly told of how Manoy dropped the whole box when he was returning (or maybe retrieving) it from the tall cabinet where it was kept out of our reach. Here it is best to say that I remember these things only vaguely, having been too young to even know how to operate the turntable.

Since then, we had forgotten already about the pono, as each of us, through the years, has gone one by one to Naga City to pursue high school and college studies.

One day in November of 1987, Supertyphoon Sisang came and swept over Bicol. At the time, I was still in Grade 6 staying with Mother and brother Ano in our house in Banat; while my brothers and my sister were all studying in Naga.

The whole night, Sisang swooped over our house like a slavering monster, and in the words of our grandmother Lola Eta, garo kalag na dai namisahan (one condemned soul). The day before, we secured our house by closing our doors and windows. But the following morning, the jalousies were almost pulverized; the walls made of hardwood were split open; and the roofs taken out. But our house still stood among the felled kaimito, sampalok and santol trees across the yard.

Among other things, I remember brother Ano retrieving our thick collection of LP vinyl records. Most if not all of them were scratched, chipped and cracked. In a matter of one day, our vinyl records had been soaked and were rendered unusable. Ano, who knew art well ever since I could remember, cleaned them up one by one, salvaged whatever was left intact, and placed those on walls as decors.

The 45 rpms and the LP circles looked classic like elements fresh out of a 1950s art deco. On the walls of our living room now were memories skillfully mounted for everyone’s recollection. And there they remained for a long time.

By this time, Mother had already bought a Sanyo radio cassette player which later became everyone’s favorite pastime.

Soon, Manoy would be glued to cassette tapes that he would regularly bring in the records of the 1980s for the rest of us. The eighties was a prolific era—it almost had everything for everyone. Perhaps because we did not have much diversion then, we listened to whatever Manoy listened to. On his boombox, Manoy played Pink Floyd, Depeche Mode, Heart, Sade, America and Tears for Fears, among a million others. Of course, this “million others” would attest to how prolific the 80s was.

In those days, Manoy recorded songs while they were played on FM radio stations. It was his way of securing new records; or producing his own music. Then he would play it for the rest of us. Music was Manoy’s way of cheering the household up—he played music when he would cook food—his perennial assignment at home was to cook the dishes for the family.

Manoy loved to play music loud anytime and every time so that Mother would always tell him to turn the volume down. Most of the time, Manoy played it loud—so that we, his siblings, his captured audience in the household, could clearly hear the words and the melodies, cool and crisp.

While Mother and Manoy would always have to discuss about what to do about his loud records playing, we, the younger ones, would learn new sensibilities from the new sounds which we heard from the sound-box. We did not only sing along with the songs being played; we also paraded nuances from them which we made for and among ourselves. Out of the tunes being played and heard, we made a lot of fun; and even cherished some of them.

When we were very young, I remember hearing a cricket when Manoy played America’s “Inspector Mills” every night, which lulled my sister Nene and me to sleep. Nene and I asked him to play it all over again because we would like to hear the cricket again and again in the said song. (Later, I would be aware that it’s not only a cricket but also a police officer reporting over the radio.)

During those nights, Mama was expected to arrive late because she worked overtime at her father’s house that hosted Cursillo de Cristianidad classes, a three-day retreat seminar which the family committed to sponsor for the barangay Bagacay through the years.

Sometimes, it was just fine even if Mother was not there when we slept. At times, we knew she wouldn’t be able to return home for that weekend, so we were lulled to sleep in Manoy’s bed listening to America and his other easy-listening music. Because he played these songs for us, the lonely nights without Mother in our house were made bearable by Manoy Awel.

When Manoy was not around or when I was left alone in the house, I would go to his room and play his records to my heart’s content. Because he would leave his other records at home, I equally devoured them without his knowledge. None of his mixed tapes escaped my scrutiny.

Through the years, Manoy would later be collecting boxes of recorded songs and later even sorting them according to artists and genres.

One day, I saw these recorded tapes labeled “Emmanuel” on one side and “Mary Ann” on the other. It wouldn’t be long when I learned that Manoy had found his better half, his own B side—in the person of Manay Meann, his future wife.