Anáyo

An pagkaákì nakatágò sa diklóm; makangálas alágad maimbóng.

Wednesday, June 18, 2025

Songs of Ourselves

All this time I have savored the timeless ballads of Matt Monro and Carpenters, have drunk much rock of say, Queen and Juan de la Cruz Band, which I have grown to love, or sometimes sipped from the modern R&B and acoustic alchemy concocted by younger songwriters and singers like Ogie Alcasid and Ne-yo. My favorites range from chanteuse Grace Nono to Paul Potts to Patsy Cline to Rico J. Puno, and the alternative Labuyo to Richard Clayderman.

Such sense of music has been influenced by people around me and people whom I grew up with—my mother, sister and brothers—my family, or better yet, our clan who sang and danced our way through life, now and then drinking from own cups.

I

How and why I have grown to like music—like every human being perhaps—I owe first to my mother, who must have adlibbed the best melodies only for me to sleep the cold nights of being left without a father. After my father’s demise, my mother’s melodies must have sounded more like elegies being sung by a widow who now as a single parent, had to fend for six growing children.

One evening, Mother told me a story of how she had to sing Victor Wood’s “Teenage Señorita” when she was being recruited for a sorority in college. I could only imagine she sang it in the corridors of Burns Hall where I first saw my very own teenage señorita Cecile Naldo, a bubbly DevCom major from Iriga who would sing the melodies of Celine Dion like an LP after our Biology class. The Celine Dion connection did not materialize much—just when my Cecilia’s singing of “If You Asked Me, Too” ended.

Mother loved Nat King Cole that whenever Manoy played “Stardust” and the rest of his collection nights after supper in Bagacay, the Banat household would be filled with her voice that sounded like it’s tiptoeing the corners of the house.

Her singing voice would delicately hit the right notes but contained “a certain sadness” that perhaps even Astrud Gilberto must have never known. Manoy recorded Cole’s collection on tapes—along with those of Carpenters and Pet Shop Boys—through our cousin Manoy Ynos’s stuff in Manila during his engineering board review in 1991.

One cool Sunday afternoon in 1993, Mother introduced me to Jerry Vale, when we were enjoying the coolness of the folding bed in our sala at siesta time. We listened to Vale’s “If You Go Away” being played on an AM radio program on the Sharp radio which Manoy bought upon her request.

She was perhaps singing away the moment thinking how to sustain in the following week her four sons studying in Naga—or perhaps she was humming away her gratitude that she was supporting only four students in the city. I and my sister stopped schooling that year.

Some seventeen years later, Mother’s swan song would be one graceful and heavenly melody, inspiring everyone in her last rites about how one single parent had weathered all odds through the years to make the best of all her six children.

II

In our brood of six, Manoy has biggest share of influence in each of us, younger siblings. While Ano and Alex also strutted their way to get our nerves equally break-dancing to the tunes of Michael Jackson and his local copycats towards the mid-1980s, Manoy’s influence in the rest of us has been indispensable.

Being the eldest, Manoy held the possession of the phonograph like the Two Stone Tablets, where the songs being played later became the sibling’s anthems. From the phonograph, everyone came to love Mother’s favorite trio the acoustic “Trio Los Panchos” whose pieces did not sound different from her aunt Lola Charing’s “La Tumba” number which she would sing during clan reunions. While Yoyoy Villame’s rpms would be played alternately with Baby Jane and Tarzan’s yellow plaka, it would be the “Santa Maria” chorus which would ring more in my memory.

Yet, the phonograph music would last only until the time when there would be no way to fix it anymore after Manoy dropped it one day when he was retrieving or returning it from the cabinet which should have been out of our reach.

Everything else in the family’s long-playing collection had escaped my memory—I would be too young to even know how to operate the phonograph. We chanced to retrieve some of LP discs in the 90s after a long list of typhoons; I could only help my brother Ano in placing them on the walls as decoration. And they certainly looked classic there—like memories pasted on the wall for anyone’s immediate recollection.

Not long after, Manoy would be addicted to tapes that he would bring in a new recorded record of many artists in the eighties. The eighties was a prolific era--with almost anything for everyone. On his boombox and other sound gadgets, Manoy played Pink Floyd, Depeche Mode, Heart, Sade, America and Tears for Fears, among a million others.

He recorded songs while they were played on FM stations on the radio. It was his way of doing things. It was his way of cheering the household up--he played music when he would cook our food--his perennial assignment at home was to cook our food. He played music on the radio anytime, everytime that Mother would usually tell him to lower down the volume.

III

Creativity or art has never escaped my second eldest brother Ano’s keen senses. In the eighties, Ano did not only have a record of break-dance tunes in their high school days in BCAT—he also made an unforgettably cool tape jacket which became a bestseller among the siblings. While Ano and Alex break-danced to their hearts’ content, we younger siblings could only look at them in amazement, later adopting their moves to our own sense of enjoyment and thrill—wherever and whenever we found avenues for it.

This time, our anthems were now being played over the Sanyo radio, the family phonograph’s successor. Mother must have acquired it through a loan presented by lending businessmen whose special offers lured a number of public school teachers in Bagacay.

Ano loved the popular music, collecting pinups from song hits of say, Gerard Joling and mounting them as frames in our sala, as if he were a familiar cousin of ours. Of course, he maintained a collection of his tapes perhaps apart from Manoy's growing collection of recorded stuffs and original albums.

IV

Then, there was a time in our lives when music would not ever be sung for a long time. Nothing demoralized us more than being poor that music must have been forgotten as pastime—as growing young adults, our needs were more of corporeal rather than spiritual—"survival," not "theatrical."

I believe when someone in a movie said that nothing impoverishes the spirit more than poverty itself. Who would not be crushed by the fact that there was not just enough to sustain ourselves? Mother’s income had never been enough so that each of us had to hum our own melodies to sing our way through our days.

But just like wine, music’s soothing properties worked wonders. While the rest of us must have found avenues to continue singing their lives, brother Alex’s quiet and restraint was music itself. In him, we would not find so much loud melodies or even singing—because such countenance solicited friendship in cousin Bong, Auntie Felia’s eldest son who played and paraded the music of the eighties like soul food. With Bong, Alex’s sense of music has been sharpened—finding their voice in the groovy and still danceable and angst-ridden mid-eighties.

Later, Alex's tight-lipped restraint significantly found its voice in the sociopath Kurt Cobain and icons of the grunge era, among others. This was the time when Bong studied medicine in Manila, while Alex pursued engineering in UNC. Nothing better could have captured his sense of isolation than the pieces of Metallica, Guns and Roses, Bon Jovi and other intimacies which he now shared with new found frat brother Nanding, our landlady’s son in Diaz Subdivision.

After 1996, reverting back to the jukebox pieces was necessary for Alex to mingle with the crowd of fellow boarders working in the busy economic zone in Laguna. After all, Michael Learns to Rock, Rockstar and Renz Verano, for instance, could certainly help bring him back to the old Bagacay, which he sorely missed. Alex would romance rock ballads even after he has established his own family in Laguna.

An Mga Ribongribong Sa Bagacay

Kun sain ako nagdakula—duman nag-iristar, nagralakaw-lakaw, asin nagurukit nin kadakul-dakul na memorya sakuya an nagkapirang mga ribongribong. An mga agi-agi sagkod buhay-buhay kan mga tawong ini kasing pamoso kaidto ni Mr. Moonlight sagkod ni Zimatar.

Haros sa kada zona kan Bagacay igwa nin turikturik. Atid-atida baya—sa Zona 1, Iraya, si Jim; sa Zona 2, Baybay 1, si Ness; sa Zona 3, Baybay 2, si Pax; sa Zona 4, Parada, si Eric; sa Zona 6, Banat, si Joe. Dangan igwa pang duwang dayo—si Gelyn na magsalang

taga-Buyo, taga-Cut 12; sagkod si Bulldog na minsan taga Zona 4, 5 or 6, o minsan nakakaabot sa Naga kalalakaw hali sa Kinali.

SI BULLDOG A.K.A. BULLS AQUINCE

Siisay an dai makakabisto ki Bulldog a.k.a. Bulls Aquince? Kun pararabas ka sa bisita pag ma-fiesta na sa Bagacay, pirmi mong mahihiling si Bulldog sa may Triangle o sa kun sain gigibohon an Amateur Singing Contest. Para sa mga organizers kan contest—kun sain

nanggana an tiyaon kong si Manay Lisa ta’ kinanta niya an “Even If” ni Jam Morales sarong mainiton na hapon—si Bulldog iyo pirmi an pwedeng mag-front act o minsan natao kan kulang na intermission number.

Sa anuman na tiripon sa barangay, siya an masasabi tang life of the party—ta’ siya “pa-oonrahan” kan mga organizers—na magkanta kan saiyang mga favoritong covers—“Boulevard ng Pag-ibig” o mga Rey Valera classics—o minsan dai. Kun maboboot an mga organizers, siya makanta nin Tagalog o English song, all in tattered outfits [basa: bara’ba an maong na pantalon, kurupas sa pirang bulan na mayong karigos, an parong

dai mo maintindihan o pero minsan maiintindihan mo—sabi ngani kan iba—“kargadong alungaang”—] tapos kun masuwerte siya, matata’wanan man nin kun anong consolation prize kan mga aki kan kapitan dangan duduhulan man nin litson sa libod kan Irmano Mayor sa may Pantalan.

Bako man talagang dakilang tambay si Bulldog. Siya garo sana sarong bisita kan kada harong kaidto. Ini man an istorya na naisabi na sana man sako kan tugang kong si Nene. Pinahawan daa ni Mama si Bulldog sa natad mi para tandanan pagkatapos. Natapos man gayod si paggabi niya pero ginuno niya sa sarosarong atis na bunga sa may natad mi. Nagutom na siguro pagkatapos maggabi kaya kinua si prutas dangan kinakan. Ano pa

garo naanggot saiya kaidto si ina mi [siguro ta’ dai man lamang nagpaaram]. Sa ina kong sarong maestra, kasa’lan nang gayo an siguro simpleng bagay. O tibaad para sa ina ko, si Buls gayod sarong normal na tawo. Siguro man gusto pa giraray tukduan ni Mama an

paragabi nin Good Manners and Right Conduct [GMRC]. Baad nagibo ni kan ina ko ta’ estudyante niya dati si Bulls—anong aram ko? O ‘baad exchange student sa Bagacay Elementary haling Buyo o Kinali. Magayon makaulay si Bulls ta’ sa pag-uulay nindo

mahihiling mo an pagkakaiba mo saiya. M aririsa mo na ika mas turikturik palan kaysa saiya. Kun sinusugot mo siya, o iniiinsulto kan kasingbata’niyang mga kaakian mga hoben sa kun sain haraling zona sa Bagacay, mahihiling mo man nanggad na sinda, an mga nagsosogot saka nagtutuya-tuya—bako si Bulldog—an mga rungawrungaw. An dai aram kan mga rungawrungaw na ini an turik na si Bulldog naiintindihan an saindang mga

katurikan. Tama. Siguro tinataram niya puro daing kamanungdanan—ta’ turikturik baya’ siya—kaya an makikiulay saiya kaipuhan maging turikturik man. Pero ano man baya an aram ta kun ano an laog kan halipot daang pag-iisip na ini?

Ta’ diyata sinusugot ta siya o dinudurulagan—dai pigtatratong normal ta’ aram tang “he’s out of our league” o “He doesn’t speak our language”. Pero mas makangirit baga kun maaraman mong mas dakul an katurikan kan ibang mga tawo sa palibot kaysa sa

sarong arog ni Bulls.

SI JOE, SARONG HENYO

Bistuha nindo si Joe, kadto daa sarong matalion na estudyante na—dakul nagsasabing si Joe, si Lena Upan, sagkod si Jim kabilang sa saro sanang batch sa Bagacay Elementary School kaidto. Sinasabi nganing an batch na ini iyo an golden batch kan eskuwelahan dahilan sa tolong henyong ini na nagkasarabay mag-iriskuwela sa satuyang alma mater. Kun dai ako nasasala, sinda na-under-an pa kan sakong mga magurang na parehong

nagtukdo sa eskuwelahan na ini—pero ini saro pang dakulang hapot na an mismong mga gurang sa Bagacay an makakasimbag sako.

Pag bangging bulanon—ini bakong iri-istorya sana kundi totoong istorya man nanggad—an ngisi ni Joe hali sa may bintana nindang capiz makakapangirabo man nanggad

sa siisay na aking gusto man magluwas mag-iba sa Aurora pag nag-agi na pasiring sa Banat. Dai man nang-aano si Joe, yaon sana siya sa may bintana, naghohorop-horop, garo iniirisip man an mga gabos na nag-aaraging kairiba sa prusisyon—mga mag-irilusyon na

nagmimirilagro sa likod, mga kantorang sirintunado sagkod garo gurutom na an boses, mga butalnak na paralak-palak na sa inutan kan andas dara-dara dangan kinakarawatan an mga karabang giribo sa daso’.

Bako lamang siyang maribok. Dai ko lamang siyang nadangog magtaram nin kun ano. Maski makasabay ko pa siya pagsakdo nin inuman na tubig sa bombahan kan mga

Bañas perang beses, mayo siya nin girong. Dakula an tulak ano pa naapod logod siya nin Bundat, katamtaman an langkaw, mataba, maitom, si Joe mayong girong pero dakul ginigibo. Mahihiling mo pa siya minsan masimba nin Domingong aga sa kapilya, puwerte an bulos, kaiba an ina niya. Tapos diretso uli sa harong ninda. Pag hapon, mahihiling mo na lang nagluluon nin mga lapang dahon kan mga star apple sa libod ninda.

Pirmi akong natatagalpo kada mahiling ko si Joe. Kan sadit pa ako—huna ko nangkukua siya nin aki tapos tinatao sa niya sa mga magibo nin tulay ta’ duman bubunu’on tapos an dugo ninda iyo an pinapanhalo sa sementong ibubuhos para daa maging pusog an tulay. Ngonyan na nahihiling ko pa siya, ginigibo an dati niya nang ginigibo—sa hiling ko an gabos na takot na idto mayo nin basehan. Sa kahaluyi kan panahon, na nakiagi man ako sa libod ninda pagsasakdo ko nin inuman.

An silencio ni Joe garong nakapagpamondo man sana saiya. Ano man daw an nasa isip niya kun nagdudurulag kami parayo saiya ta’ aram ming siya si Joe? Baad gusto man sana kaidtong makiulay pero mayong nagrarani siya ta’ turikturik ngani daa siya. Ano man daw an namamati kan sarong arog ni Joe? Siguro nasobrahan daang adal o basa, sabi kan saro kong kaklaseng taga-Banat, mayo siyang ibang makulay kundi sadiri niya. Ano man daw an namamati niya kun rinarayuan siya nin kadaklan na normal na tawo? Siguro namomondo siya. O mas nabubuabua ta’ mayo nang nakikiulay saiya, apuwera kan pirang tawong aram na puwede man siyang kaulayon siring sa sarong normal.

SI JIM, SARONG ERMITANYO

Si Jim sarong parasira na taga Iraya. Sarong heartthrob kan kapanahunan niya—an dungo sa mestizo, an mata sa Intsik, nakasulot pirmi nin itom na T-shirt—bara’ba’, dangan an short na maong na tinarabas—mayong kapareho an style niya nin huli ta’ an barungot niya tugmang-tugma sa mga tursidong rinaralayog kan duros pag na-lakaw na siya sa may

tinampo. Fashion model an lakaw ni Jim—dawa bara’ba an saiyang bado. May tindog kumbaga; tapos an lakaw niya, saiya lang talaga. An pagbaya’ kan wala niyang bitis

sa toong bitis, mayo nin kapareho. Lean an hawak ni Jim, an itsura niya mayong pinagkaiba sa mga Shaolin Master sa nadadalan mi sa Betamax kaidto ka Auntie Felia. An buri niyang kopya bara’ba man. Fashion-wise, consistently elegant sagkod stylish an su’lot ni Jim. Totoo—maati siyang hilingon ta’ an itsura niya garo pirang aldaw nang dai nagkarigos pero dai ka—ta’ minsan an itsura niya—garo pirming bago siyang karigos.

Dai ko pa nabakalan si Jim kan sira niyang tinitinda pero nahihiling ko siyang nagpapara lakaw-lakaw na garong linilibot an barangay—minsan nakapamulsahan sa maong niyang shorts, nakaduko na garo kadakuldakul siyang iniisip—kadakuldakul an saiyang iniisip na dai mo siya makaulay ta’ okupado baya an payo niya. Minsan nasabatan ko siya kaidto—dai ako natakot maski ngani aram kong turik daa siya. Palibhasa dai man nang-aano;

dai ako nagdalagan parayo o nag-iwas saiya. Daradakula na man kaya palan ako kaidto, pero nahiling ko na man kaidto na maboot si Jim. Serene and composed kumbaga.

Kayang darahon an sadiri. Garo ermitanyo an hiling ko saiya kaidto, maski ngonyan. Ibang klaseng ermitanyo ta’ kairiba siya kan mga tawo.

Pag nag-aagi siya sa may parada, dai man napupugulan kan mga tawong hilingon an itsura niya, dangan an mga gurang masarabi sa mga pastidyong aki, “Hala, kun dai ka mapondo, ipapadara ta’ ka ki Jim. Kukuanon ka niya, kaya alo na.” An aki pusngak pa pero aram na niya an pagkatawo ni Jim. Nungka pa man maipalaiwanang ni Jim sa saiya na ‘baad man sana iba an iniisip niya.

Matino siguro si Jim. Haloy-haloy nang panahon arog siya kaiyan—parasira, paratinda nin

sirang pigpangkehan—nakakaraos man na mabuhay. Digdi ta mahihiling na maski an mga turikturik dai ligtas sa ekonomikong realidad—na kaipuhan magtrabaho ta nganing igwang kakanon—mag matino ka o mag tinurik ka man. Puwede mong masabi na kaya si Jim naturik ta’ dai niya maako an realidad na an ibang mgatawo mayayaman—nakaistar sa mga garo simbahan na mga harong—pati an saindang mga gadan—ilinulubong sa mga

harong na garong mga subdibisyon. Makabua bagang maray.

AN MAYONG PAGAL NA SI PAX

Sarong hoben [pero an itsura niya gurang na] na lalaking taga-Baybay na may Down’s Syndrome, iba man an itsura ni Pax sa mga inaapod na mongoloid. Siya maitom, dakulang lalaki, wi’wi’ an nguso, may su’lot na bandana, nagpaparasakdo nin inumon na tubig sa

Burabod para sa mga taga Baybay.

Siya sarong oripon na may dignidad. Dai mo sana maaraman kun pirang litrong tubig siguro an utang saiya kan mga taga babybay na nagpapasarakdo saiya sa Kalye Maribok. An padyak niya na tinauhan kan mga partidaryo niyang mga Nacorda iyo an pinapansustinir niya sa solo solo niyang buhay. Magngalas ka man nanggad kun mas may kaya si Pax ki Bulldog, dawa ngani mas hagbang asin purusog an hawak ni Bulldog saiya.

Si Pax magalang, nagbibisa sa mga gurang, nakikikawat sa mga aki, maski ngani pigpapara-rawrawan si Pax kan mga mas buang daing karakarigos na mga kahobenan sa

Triangle. Pirmi man nagsisimba sa kapilya kun Domingo. Pero kan naging bihira na an misa sa Bagacay ta’ an barangay daa sabi kan padi sakop pa kan mas dakulang parokya kan Manguiring, arog kan ibang parasimba sa Iraya, nagkararaya na man sana dangan dai man nanggad maibalik an dating numero kan mga nagsisirimbang Katoliko. Masakit man siguro kun mapa-Manguiring pa si Pax para sana magsimba. An hadit kan partidaryo niya

dai mo man masimbag.

SI ERIC A.K.A. KABAKAB

Kun ki Eric mo maibabagay an kasabihan na “Aki pa, gurang na; gurang na, aki pa,” saiya mo man giraray masasabi na “an aki kun pag dakula aki pa man giraray an pag-iisip sarong biyaya sagkod grasya hali sa Mahal na Diyos.”

Naka-pajama, nagraralaway, sagkod mu’riton an lalawgon, kulot an buhok, birilot magtaram pero sige sanang taram ta’ dai man pula. An mga pinsan kong

babayi an durulag pirmi pag nagdadalagan na si Eric, nagpaparapanhapag nin babayi para man sana suguton. Pero pag-inanggotan man kan gurang, napapakiulayan man

baga. Palibhasa aki pa kaya dawa ngani tinedyer na man. Kaidad ko sana si Eric—kuta na mag-aaagom na man siya ngonyan na mga taon. Minsan pa ngani pigsusurugot

mi sinda na ipapadis mi Ki Eric kun dai mauruli sa harong pag oras nin orasyon. Si Eric nagbibisa sa mga gurang, nagtataong-galang sa anuman na tiripon kan mga gurang—lamay sa gadan, novena ki Santa Maria, o miski maprusisyon para ki San Antonio de Padua.

Arog kan ibang mga aki—minsan ngani bakong arog kan ibang mga aki diyan—si Eric bibong aki. Daing palta siya kaiba an ibang kaakian—nagchachacha o nagirikid-ikid sa baylihan sa sinasabayan an “Ice, Ice, Baby” o “You’re My Heart You’re My Soul” kan Modern Talking, o kun ano man na disco tune ni Ken Laszlo kaidto. Siempre pagal-pagal na man si Eric kababayle bago pa man magsaraksakan an mga dayong taga Tigman o Mananao sa laog kan baylihan sa Triangle. Dai man ako mangalas kun pati ngonyan, sinasabayan pa ni Eric an Destiny’s Child o Black Eyed Peas pag pinatugtog sa bagong baylihan sa covered multipurpose hall sa pantalan. Arog na sana kaiyan an pagka-sociable ni Eric.

Nasasabotan ni Eric an kultura kan Bagacay—sa kahaluyi kan panahon natuod na man siya sa mga Katolikong ritwal kan mga gurang sa barangay. Nahihiling an biyaya nin Diyos sa arog niya kun mahihiling mo siyang nagpapangadyi sa kapilya kun Domingo—kaiba kan saiyang mga magurang. O minsan sa Flores de Mayo kan lolahon ko, amay na amay pa yaon na sa atubang kan altar, may darang mga gumamela, kanda, o manlaen laen na

burak—arog nin iba pang aki. Ogma na pagkatapos kan pangadyi sagkod rosaryo, an tandan na galleta, tanggo, o sopas na maaskad bastante na sa kaogmahan kan aking arog niya. Naggugurang na an hawak ni Eric pero dai naghihira an pag-iisip niya. Sa prusisyon pag fiesta, kun yaon siya sa baylihan kan bisperas, pagkaaga yaon man siya sa prusisyon para sa patron—minsan may darang kandila o minsan naiinot sa gabos na nag-puprusisyon, garo bagang siya an giya [marshall] kan paganong ritual na ini. Sa mga

religious activities, pirmi nang mas perfect attendance si Eric kaysa sa ibang mga aking kairidad niya.

Si Eric produkto kan sarong kulturang Bikolano, Katoliko, relihyoso, sagkod pilosopo. Nakua niya an bansag na Kabakab sa saiyang ama—na nabansagan kan gabos na tawo sa barangay. Sa lugar man lang na ini nakukua niya an ugaling parasogot, para-po’ngot,

pasaway. Sinosogot siya kan konduktor ni Magan kun maagi siya sa pantalan, hinuhubaan kan mga hoben na parabasketbol hali sa Triangle, pig-iiwal kan mga aking habo siyang paayunon sa turubigan sa may tinampo. Aki baya, namamana man sana ni Eric an

kaanggotan sagkod an kakanosan kan kinaban. Sa komunidad man lang na iniidong-idongan kan saiyang halipoton na pag-iisip nakukua niya an mas halipot—ta’ abaanang kakipot kan—pag-iisip na ini.

Kaipuhan niya man nanggad maging kabakab—sarong talapang na mahalnas, mabilis, sagkod maulyas—nganing makalukso siya parayo sa mabatang lapok na iniistaran

niya na iyo an Bagacay.

AN BABAYING SI NESS

An gayon kan babayi nahihiling sa pagdara niya kan sadiri sa tahaw kan mapantuyaw na komunidad—sa lugar na an lalaki na sana an kagdaog. Si Ness nagtitinda nin sira sa entirong barangay—mahihiling mo siyang naglalakaw luto-luto an nigong may laog nin la’bas na abo, langkoy, o minsan balaw. Nakapalda, maniwang, maitom, mahimpis an hawak—nagtitinda nin sira si Ness pag mahapon na.

Pero dai ko pa lamang siyang nadangog na nagkurahaw sa mga tawo para ialok an tinda niyang sira. An aram ko, pag yaon na siya nagdadangadang sa mahiwas na tinampo

sa Bagacay sa may highway pasiring sa may eskuwelahan, aram na na siya may tindang sira sa luto-luto niyang nigo. Minsan si May Biday an natatangro kan pirang atadong abo o pagotpot, kaya lugod an mga Buban, mga Belga, sagkod mga Panis presko an kosidong pangudtuhan pagkatapos magsaramba na Joshua sagkod ni Dorcas sa Protestanteng kapilya sa Banat.

Kun may bagyo, an payag payag ni Ness harani sa may baybayon binabayo kan duros na garo baga sarong baraha sa ta’ta’ na pig-iiriwalan kan limang gurang na parasugal sa Iraya—dai pusog an nipa sagkod an posteng coco lumber. Haros iralayog an mga latang atop. Pero pagkatapos kan bagyong uminagi sa Bagacay, mahihiling mo si Ness sarong aldaw naglilibot nin sira—nagtatangro sa mga kataraid, para may maisira sa saindang kakanan.

O minsan daa, pagkatapos kan bagyo, madadangog si Ness kan mga kataraid na nagkakanta—magayonon an boses, sa ralabot nang harong, sa inaratong nang kasangkapan sa harong, yaon sana diyan—nagkakanta. Dai mo aram kun

siya nag-oomaw sa Diyos ta dai siya naatong asiring sa dagat, o tibaad linalamuda an duros sagkod an uran.

SI GELYN, AN BABAYING NAKAPULA

May sarong Lady in Red na an pangaran Gelyn. Kun ta’no inapod ko siyang lady in red—maiintindihan nindo ngonyan. Sarong hapon, kan ako sinugong may bakalon na mirindalan sa tindahan na Bago, dai ako nakadagos sa may triangle ta’ yaon daa duman si Gelyn, nagpapasali, o napaparataram. Ano pa naghikap ako sa may tindahan na Lola Mimay sa atubangan na Agor. Takot-takot ako ta’ dai ako makakaagi sa Triangle. Habo kong mahiling si Gelyn ta’ ‘baad ano an gibohon sako. Dai ko na matandaan kun nakadagos ako sa bisita. An aram ko sana an takot ko ki Gelyn daing siring na sana—ta’ garo

pati naiimahinar ko an mata niyang burulakog nakahiling sakuya na garo ako kakakanon.

An aram ko si Gelyn hoben pang babayi na nakasulot nin makokolor na bestida—dati gayod na maputiputi pero nagparaitom na sana ta’ sige sana daang lakaw hali sa

bukid pasiring sa maski sain sain. Mayo na akong nadangog pang iba manongod saiya. Kan ako nagdakula na, dai ko naman siya nahihiling.

Siring kan Dose Pares, mga CAFGU sagkod CHDF, si Gelyn basang na sana man nawara sa Bagacay. Garo mayo ka na man madangog manongod saiya. O arog kan ibang mga dayong negosyanteng nagtirinda sa Triangle kaidto tapos nagkawarara na sana kan kasagsagan kan mga Dose Pares saka mga nagroronda sa mga NPA, hain na man daw

si Gelyn ngonyan?

Sa gabos na mga buhay kan mga tawong ini, an deskripsyon na “halipot na pag-iisip” para sa sarong turikturik sarong misnomer, o salang pag-apod sa mga arog nindang nagkasarambit asin an mga dai ta’ pa mangaranan na mga turikturik na nagparalakaw lakaw sa magayonon, madoroson, asin mahiwason na Bagacay kun sain ako nabuabua kadudulag, kakadalagan parayo sainda. Aki pa ako kaidto. An paghiling ko sainda

mayong pinagkaiba sa paghiling ko sa mga mumu pag banggi na sa may Banat, na naghaharapag sakuya pag sinusugo akong magbakal ni bitsin para sa kinusidong

abo’ ni Manoy. An dai ko aram kaidto—sa pagdulag ko sainda ta’ ako aki pa—nagdulag ako sa sarong posibilidad na puwede man sanang gibohan nin paagi tanganing ma-apreciar o maintindihan.

“Ta’no daa ta’ dai na man sana daa pabayaan an mga turikturik na maging turikturik?” Pati privacy man ninda dai na lamang daa ginagalang—nin huli ta’ sinda turikturik na, iyo na yan sinda kaiyan—dai mo na man daa dapat pang ilangkaba sa intirong komunidad na sinda man nanggad turikturik. Igalang na man daa dapat an pagigi nindang turikturik. Mas kapakipakinabang gayod na itratong tama an mga turikturik kan mga tawong mas matitino. Kun dai, an mas matitinong tawo an totoong buabua.

Sa sarong kanta na pigpapara-interpretar nin ribong [ribong na] beses kan mga contestants sa Miss Bagacay, Miss Tinambac, Miss Hinagyanan, o Miss Karangkang, o maski gayod Miss Cadlan, an parakanta naghahapot, Sinong dakila?/Sino an tunay na baliw?/Sinong mapalad? Sinong tinatawag mong hangal?/Yaon bang isinilang/Na an pag-iisip ay ‘di lubos/O husto an isip/Ngunit sa pag-ibig ay kapos?

Iyo man nanggad, ano? Sarong dakulang katurikan na an talento na puwedeng ipahiling kan sarong magayon na daraga iyo man daa an magbinua. Apuwera kan magkakan

nin kalayo, o magsapa’ nin bonot, bako na man gayod talento an magpanggap na dai ka man daa bua, bakong iyo?

Siisay pa man daw an mas bua sa sarong daragang taga-Irayang nagpabados sa may agom nang taga-Baybay? Siisay man nanggad an buabua? An closet na bakla na

nan-abuso kan saiyang sobreno? An kuraptong kapitan? An kagawad na igwang sambay sa Tigman? O an pusikit na palpal sagkod parasugal na Irmano Mayor?

Sa saiyang Madness and Civilization, nabuabua an sarong Pranses na si Michel Foucault sa kasasabing an mga turikturik bako an mga bata’ kan sarong komunidad kundi iyo an biktima kan mga kapalpakan kaini. Kun sa Europa kan mga panahon sagkod ngonyan, an mga turikturik priniriso—kinurulong ta’ sa hiling kan matitinong gobyerno mayo sindang lugar sa publiko—sa Bagacay an mga turikturik nagkairibahan kan mga normal

na tawo—asin ta’ an mga taga-Bagacay iyo logod naapektuhan, nagkaurulakitan kan kakapayan ka mga turikturik na ini.

Halimbawa, an mga aking arog mi nagdarakula bagang tarakot saindang mga persona. Saradit pa kami—tinatarakot kami kan mga turikturik na garo dai man, kan mga multong marayo man. Nungka kami sinarabihan na an mas likayan iyo an kapitan na gumon

sa ilegal na mga aktibidades sa barangay. Na dapat mas paghandaan an madadayang paratinda nin alang sa talipapa’. Na dapat mas likayan an mga adik na rinarasyunan nin shabu sa Baybay—o mga NPA na puwedeng mag-aragi sa likod kan harong mi paduruman sa Katangyanan pagkatapos i-salvage an sarong informer na nagbalik-loob na. Sala baga an itinurukdo samuya.

Hinarabon na sa mga lumbod ming isip an posibilidad na an turikturik mas maboot sa normal na tawo. An trabaho mi iyo an halion an salang pagpagamiaw na ini. Iyo ni

an nakapagpogol sa mga ideya mi, sa mga isog ming kaipuhan lalong lalo na ngonyan na mga panahon na kun bako kang maisog o desidido sa sarong bagay—mayo kang

magigibong kapaki-pakinabang sa buhay mo. Dangan interesanteng pagparausip-usipon ini ta’ sa kahaluyi kan panahon mayo sa sainda an ipinaintriga man lamang

sa sarong mental institution. Ma-bilib ka sa mga kapamilya ninda ta’ dai man lamang o winaralat sa kun sain an saindang tugang, aki, tiyuon o hijado na aram

nindang igwang diperensya an pag-iisip.“He aint heavy; he’s my brother” sabi ngani kan sarong folk song—tama, nin huli ta’ kadugo ko siya, dai ko siya puwedeng

pabayaan o ipaubaya na sana sa ibang tawo.

Sa Bagacay naipagamiaw sakuya na an kinaban kan mga turikturik sarong kahiwasan nin pagkadakuldakul na posibilidad. Sa mga buhay-buhay kan mga arog ni Joe, Gelyn, Jim,

Bulldog, Pax, asin an riboribo pang ribongribong sa Bagacay, dakul na mga bagay an puwedeng mangyari—dakul an puwede tang mahiling, puwede tang madangog, puwede

tang masabi, asin—magtubod ka sa dai—puwede tang maintindihan.

Songs of Ourselves: Fragments

If music is wine for the soul, I suppose I have had my satisfying share of this liquor of life, one that has sustained me all these years.

All this time I have savored the timeless ballads of Matt Monro and Carpenters, have drunk much rock of say, Queen and Juan de la Cruz Band, which I have grown to love, or sometimes sipped from the modern R&B and acoustic alchemies concocted by younger songwriters and singers like Ogie Alcasid and Ne-yo. My favorites range from chanteuse Grace Nono to Paul Potts to Patsy Cline to Rico J. Puno, and the alternative Labuyo to Richard Clayderman.

Such sense of music has been influenced by people around me and people whom I grew up with—my mother, sister and brothers—my family, or better yet, our clan who sang and danced our way through life, now and then drinking from own cups.

I

How and why I have grown to like music—like every human being perhaps—I owe first to my mother, who must have adlibbed the best melodies only for me to sleep the cold nights of being left without a father. After my father’s demise, my mother’s melodies must have sounded more like elegies being sung by a widow who now as a single parent, had to fend for six growing children.

One evening, Mother told me a story of how she had to sing Victor Wood’s “Teenage Señorita” when she was being recruited for a sorority in college. I could only imagine she sang it in the corridors of Burns Hall where I first saw my very own teenage señorita Cecile Naldo, a bubbly DevCom major from Iriga who would sing the melodies of Celine Dion like an LP after our Biology class. The Celine Dion connection did not materialize much—just when my Cecilia’s singing of “If You Asked Me, Too” ended.

Mother loved Nat King Cole that whenever Manoy played “Stardust” and the rest of his collection nights after supper in Bagacay, the Banat household would be filled with her voice that sounded like it’s tiptoeing the corners of the house.

Her singing voice would delicately hit the right notes but contained “a certain sadness” that perhaps even Astrud Gilberto must have never known. Manoy recorded Cole’s collection on tapes—along with those of Carpenters and Pet Shop Boys—through our cousin Manoy Ynos’s stuff in Manila during his engineering board review in 1991.

One cool Sunday afternoon in 1993, Mother introduced me to Jerry Vale, when we were enjoying the coolness of the folding bed in our sala at siesta time. We listened to Vale’s “If You Go Away” being played on an AM radio program on the Sharp radio which Manoy bought upon her request. She was perhaps singing away the moment thinking how to sustain in the following week her four sons studying in Naga—or perhaps she was humming away her gratitude that she was supporting only four students in the city. I and my sister stopped schooling that year.

Some seventeen years later, Mother’s swan song would be one graceful and heavenly melody, inspiring everyone in her last rites about how one single parent had weathered all odds through the years to make the best of all her six children.

II

In our brood of six, Manoy has biggest share of influence in each of us, younger siblings. While Ano and Alex also strutted their way to get our nerves equally break-dancing to the tunes of Michael Jackson and his local copycats towards the mid-1980s, Manoy’s influence in the rest of us has been indispensable.

Being the eldest, Manoy held the possession of the phonograph like Two Stone Tablets, where the songs being played later became the sibling’s anthems. From the phonograph, everyone came to love Mother’s favorite trio the acoustic “Trio Los Panchos” whose pieces did not sound different from her aunt Lola Charing’s “La Tumba” number which she would sing during clan reunions. While Yoyoy Villame’s rpms would be played alternately with Baby Jane and Tarzan’s yellow plaka, it would be the “Santa Maria” chorus which would ring more in my memory.

Yet, the phonograph music would last only until the time when there would be no way to fix it anymore after Manoy dropped it one day when he was retrieving or returning it from the cabinet which should have been out of our reach.

Everything else in the family’s long-playing collection had escaped my memory—I would be too young to even know how to operate the phonograph. We chanced to retrieve some of LP discs in the 90s after a long list of typhoons; I could only help my brother Ano in placing them on the walls as decoration. And they certainly looked classic there—like memories pasted on the wall for anyone’s immediate recollection.

Not long after, Manoy would be addicted to tapes that he would bring in a new recorded record of many artists in the eighties. The eighties was a prolific era--with almost anything for everyone. On his boombox and other sound gadgets, Manoy played Pink Floyd, Depeche Mode, Heart, Sade, America and Tears for Fears, among a million others.

He recorded songs while they were played on FM stations on the radio. It was his way of doing things. It was his way of cheering the household up--he played music when he would cook our food--his perennial assignment at home was to cook our food. He played music on the radio anytime, everytime that Mother would usually tell him to lower down the volume.

III

Meanwhile, creativity or art has never escaped my second eldest brother Ano’s keen senses. In the eighties, Ano did not only have a record of break-dance tunes in their high school days in BCAT—he also made an unforgettably cool tape jacket which became a bestseller among the siblings. While Ano and Alex break-danced to their hearts’ content, we younger siblings could only look at them in amazement, later adopting their moves to our own sense of enjoyment and thrill—wherever and whenever we found avenues for it.

This time, our anthems were now being played over the Sanyo radio, the family phonograph’s successor. Mother must have acquired it through a loan presented by lending businessmen whose special offers lured a number of public school teachers in Bagacay.

Ano loved the popular music, collecting pinups from song hits of say, Gerard Joling and mounting them as frames in our sala, as if he were a familiar cousin of ours. Of course, he maintained a collection of his tapes perhaps apart from Manoy's growing collection of recorded stuffs and original albums.

IV

Then, there was a time in our lives when music would not ever be sung for a long time. Nothing demoralized us more than being poor that music must have been forgotten as pastime—as growing young adults, our needs were more of corporeal rather than spiritual—"survival," not "theatrical."

I believe when someone in a movie said that nothing impoverishes the spirit more than poverty itself. Who would not be crushed by the fact that there was not just enough to sustain ourselves? Mother’s income had never been enough so that each of us had to hum our own melodies to sing our way through our days.

But just like wine, music’s soothing properties worked wonders. While the rest of us must have found avenues to continue singing their lives, brother Alex’s quiet and restraint was music itself. In him, we would not find so much loud melodies or even singing—because such countenance solicited friendship in cousin Bong, Auntie Felia’s eldest son who played and paraded the music of the eighties like soul food. With Bong, Alex’s sense of music has been sharpened—finding their voice in the groovy and still danceable and angst-ridden mid-eighties.

Later, Alex's tight-lipped restraint significantly found its voice in the sociopath Kurt Cobain and icons of the grunge era, among others. This was the time when Bong studied medicine in Manila, while Alex pursued engineering in UNC. Nothing better could have captured his sense of isolation than the pieces of Metallica, Guns and Roses, Bon Jovi and other intimacies which he now shared with new found frat brother Nanding, our landlady’s son in Diaz Subdivision.

After 1996, reverting back to the jukebox pieces was necessary for Alex to mingle with the crowd of fellow boarders working in the busy economic zone in Laguna. After all, Michael Learns to Rock, Rockstar and Renz Verano, for instance, could certainly help bring him back to the old Bagacay, which he sorely missed. Alex would romance rock ballads even after he has established his own family in Laguna.

Summer

Quiet, calm afternoons bring me back to my afternoons in our old house in Bagacay. To avoid the baking heat of the rooms, I often lay down on the canopy of our rooftop, safe under the eaves. There, I fell asleep until a cooler breeze from the backyard of the Absins, our neighbors who owned the house at the foot of the hill, woke me up. The late afternoon was the best time to linger, then someone from the house, Mother, brother, or sister, called me for an afternoon treat of linabunan na batag or gina’tan.

Flores de Mayo

Mio Hermano Intimo

Agosto 2007

Bagacay, 1942

Kan si Rafael San Andres mga pitong taon pa sana, dahil naman gayod sa kahisdulan, igwang nakalaog na crayola sa saiyang dungo. Mga pirang aldaw an nag-agi, mala ta maski ano an gibohon kan ina niyang si Visitacion, dai nanggad mahali-hali an crayola sa dungo kan aki.

Kan bulan na iyan, Mayo, igwa nin pa-Flores si Visitacion sa saindang harong sa Iraya. Dawa na ngani gayod makulugon ang dungo, nin huli ta igwa baya nin tandan na sopas na tanggo saka galleta an mga aki, nagbale sa Flores si Rafael.

Sa saday na harong ni Visitacion, an mga aki minadarara nin mga sampaguita, gumamela, dahlia, dahon nin cypres na ginurunting na saradit. Maparangadie muna an mga gurang mantang an mga aki nakaturukaw sa salog. Dangan maabot sa cantada an pagpangadie ninda sa Espaniol. Dangan maabot sa parte na an mga aki masarabwag kan mga dara nindang burak sa altar ni Inang Maria. Magkapirang beses masabwag an mga aki nin mga burak segun sa cantada.

Sa mga pagsabwag ni Rafael kan saiyang mga burak sa altar, basang na sanang tuminubrag hali sa dungo niya an crayola. Nagparaomaw si Visitacion asin daing untok na nagpasalamat sa nangyari. Nin huli man sa nangyari, nangayo-ngayo si Visitacion na gigibohon kan pamilya an Flores de Mayo sa masurunod pang taon bilang pasasalamat sa pagkahali kan crayola sa dungo ni Rafael.

Poon kaidto sagkod ngonyan, pinapadagos kan pamilya ni Visitacion San Andres an saiyang panata na dae mababakli ni isay man. Hasta ngonyan, tinutungkusan kan pamilya San Andres an pasasalamat kan saindang mga apoon, patunay na binibisto kan tawo an karahayan kan Mas Nakakaorog.

O, Clement, O, Loving, O

Remembering Clemente T Manaog [1910-1986]

Today I remember--some twenty years ago--my father's father who succumbed to a lingering illness he had had for a long time.

Some two decades ago today, our eldest brother Manoy Awel, along with Uncle Berto's eldest daughter Manay Gina, stood long hours for him in his deathbed.

In more ways than one, Lolo Ente was our refuge. Mama frequently sought help from him especially in the most challenging days of solely bringing up her six children. Quite a feat for our mother, really. Clemente's son Manuel died in 1978, some eight or nine years before he himself left this world.

Clemente Taduran Manaog--born in 1910--said to belong to a lineage who pioneered clearing the land and "started civilization" in barangay Banao in Iriga City most probably even before it became a city--was a farmer whose simple and humble life lived with his equally magnanimous wife Rosario Monge Cepe, had not failed to inspire their seven children to strive hard and succeed in their chosen fields.

Clemente's two sons became members of the police and the military--Uncle Idong and Uncle Edmundo; four became public school teachers and servants--Auntie Cita and Adang Ninang, my Uncle Berto and my father Manuel; while his second eldest son Uncle Milo followed his own footsteps as a farmer.

I remember my grandfather's simple, dark but cozy room where he stayed in 128 and feast on exotic food prepared by the "iron chefs" of Banao. Such priceless moment is always something to go back to. Someday. Someday.

During vacation days, Lolo Ente would visit Bagacay from Iriga and bring us to the sea after visiting the tomb of my father. After prayers and rituals in my father's tomb, he would take us to swim in the beach near the cemetery, a familiar place I would later call The Sea House.

I remember how I was once thrown to the water along with my cousins, but I managed to swim up to where Lolo Ente was. The water looked dark and abysmal--it was blurred but warm. Young as I was, I was too afraid to swim that the experience had not been enough to make me learn to swim sensibly at all.

During his visits to Bagacay, Mentz, Nene and I would show Lolo Ente our good papers in grade school--from grade one until 1985 or at that time. He'd be so happy to look at them. In fact, he would really get our class papers graded "100%" or "Very Good" in exchange for a particular sum of money.

Although this would be enough to send us to Lola Mimay's store where we would buy balikutsa and Burly, it is interesting to know what he would do to these purchased products. Lolo Ente would use our papers, these precious proofs of our outstanding performance in school as his toilet paper.

Most of my Writing papers under Mrs. Cornelio must have ended up with Lolo Ente's moments catering to his call of nature. Very well earned, indeed. Interesting that our lives as "businessmen" already started when we were young.

I just want to stop writing here or else I would really want to cry. So long for a grandpa's life well lived with his orphaned grandchildren.

I can just wish I could retrieve Lolo Ente's last letter to mother written in two or three pages of tablet paper which he sent through Manoy Awel some twenty years ago.

If I can just recall it right, Lolo was very much saddened by our poor situation back in the Bagacay house--where his son's widow, our mother, the sole parent of six growing children, scrimped and scrammed just to make ends meet. Just to make ends meet.

But I suppose the same letter also came with a half sack of rice or so and other fruits or crops which were harvested from the old man's farm where he toiled with his own blood, sweat and tears for his grandchildren who were far away from him.

The old man must have missed them dearly as much as he must have badly missed his son Manuel, their father who was gone too soon, too early.

Clemente's son Manuel's college graduation picture, Mabini Colleges, Iriga City, 1965

But as they say, God's time is never our time. So I just repose and say--all things must have happened for sensible purposes--and everything happens right in God's own time. In his time.

May God bless your kind, loving and warmhearted soul, Lolo Ente.

Eternally.

Amen.

Cancion Kan Taga-Bagacay

I

Mga aki sa Bagacay kun dai nag-iiriskwela,

minsan nagkakarawat, o nagkakara-karanta

Kaibahan kan mga magurang ninda

Sa radyo maghapon dangog nin drama—

Mayo na gayod hahanapon pa ta gabos yaon na—

Presko an duros, nag-uuran sa may harong

Magurang, pinsan, kahoy, mga dahon

May ayam, may ikos, may orig sa tangkal

Pagkatapos kan lumlom, may init an saldang,

Pag bakasyon, may aurora, o pabayli,

Pag habagat o aya-ay, may pabiga', pasali.

Sa pamilya, magayon an iribanan,

Mayong turuklingan; nagkakairintindihan;

Nag-iirinuman—pag naburat, bagsak;

Pag dai nakabangon, kabaong.

Urutangan, siringilan, murulestyahan,

Minsan sirilyakan ta’ dai nagkakadarangugan

Pero maugma ta’ abang prangka

Mayo kitang masasabi ta’, basta.

An kalbo pugo man giraray;

An kawayan butong man giraray;

An mga aki mayong kalson man giraray.

An may buhok nabubulugan man; an nagtitinda nabebentahan;

An nalilipot naiimbongan; anuman na mainit nayeyelohan;

An naglalantuag nakakauli man; an may helang inaaswang.

An siisay man na gutom nagkakakan—

Kun bakong gina'gang karne, mahamis na ginatan;

Mirindalan pinakro, bulgur, sinuman;

Pulutan, kutsinta, kun ano na sana man.

II

Sa sugalan, mga gurang tiripon lalo na kun hapon,

May nagtitinda pang sitsaron; sa tindahan, mamon.

Sa binggohan, kadaragahan o may mga agóm urumpukan.

An mga aki sa magurang aba anang pakinabang—

Sa laog kan harong, o sa tindahan,

Linilibot an lahot hanggang sa simbahan.

An putong tinitinda uurutangon;

Mauli an aki sirisingko an gugom; Nom!

Bagas na pamanggihan mayong tutungudon.

An mga omboy makunswelo man

Nahulog sa hagyan, nabakros an laman;

Kun mayong tipdas, kinukumbulsyon,

Kun bakong lugadon, maniwangon;

Garo mga talapang; mga tulak darakulaon—

Urugmahon dawa gurutom.

Mga daraga kapot an komiks maghapon

Mga soltero pugapo, sugpo papabakalon,

An mga ama sa pantalan maghapon—

Baggage o labor sa lantsang pa-Siruma-hon,

Bani, Popoot, mga biyahe pag sinárom.

Pag-uli kun hingaw, problema yaon;

Kun burat, iiwalon an agom;

An masaway magurang o tugang kan agóm.

Pag nagkakurulugan, harabuan;

Malayas, mabuwelta; may nalingawan na kwarta,

An mga aki dara, et cetera.

III

Maestrang sa high school bakasyon na, dai pa nag-uli ta’ siya

Saka estudyanteng taga Iraya nagkairintindihan na;

Nagkairiyuhan, mayong napugulan; pag uban-uban, turuytuyan,

Burunuan, harandaan; mga abay paturuyatoy sa simbahan.

Pero dawa arog kaini, Marhay an buhay ninda digdi—

Nakangirit kadaklan sainda; sa saro, dai ka magsuba-suba

Ta’ pag napasala ka, nya! Pasensya!

Hali sa dagat an bahod dangog-dangog

An mga parasira biyong nag-aaranggot

Ta’ mayong pasayan; tikong an nadakop

Sa Mauban mauran; dakulaon an bahod.

An langit sa bukid abang lumlom

An bagyo yaon na daa sa Quezon

Tapuyas sana man daa,

Pero nagsasalimagyo na baga!

Pag nagbaha na, dai ka magluwas

Kun habong maingas o mabasa nin tapuyas;

Ta’ pag maanayo, masakit ipatawas;

Mahal; an presyo kan bulong makangalas.

Kun aya-ay na, an banggi malipot;

Mayong niisay man na naaanggot—

Paraoma, sungo an hakot; parasira, saklay an hikot;

Mga aking sinusurugo pag banggi, tarakot;

An tinampo mahalnas; sa harong mapulot.

An lugar na ini habong halian ta’ marhay an pagkakan

Maski ralabot an istaran nakakaraos man.

Basta butog an tulak an isip daing hugak

Mayong maraot ta’ dai ka maaanggot.

IV

Kun pista, urugma; o dawa Kwaresma

May salabat o galleta an nagpapabasa.

Mga ilaw kan poste pundido daa

Pero naglalaad kun aga, baterya

Pag banggi na nauubusan daa—

Kaya madiklom, malipot

Sa harong an agóm maimbong;

Daing kasing na’góm.

Sa pag-agi kan aldaw

Pu'on kan santol minarambong

Kaya sa harong madoot, madahon;

May hinilunuhan kun maation—

An sawa pag nadakop, asalon;

Pag tinuka’ ka, kinyentoson.

Magsalang basog, gutom;

Kun bakong mataba’, helangon;

Kun mayong agóm, poro’ngoton;

Kun daraga, nakaporma;

Kun daragang gurang man, nakasaya;

Kun mayong sambay, relihioso;

Nin huli ta Hermano, politiko.

Digdi samo sa Bagacay

Ordinaryo an buhay, simpleng maray—

Mayong gayong problema

Apuwera kwarta, kun tinitikapo na.

Daing kaartehan, mayong lilikayan

Mayong aalanganan, mayong aralanganan.

Sunday, May 22, 2022

Dakulang Kalugihan

Dakul an kalugihán kan mga estudyante nin huli kan pandemyang ini. Bakò tà dikit o mayo sindang nanonòdan sa mga module na itinatao o sa Google Classroom na pinapagibo.

An pagkanood ngonyan gamit an module o internet yaon sa sadiri nindang panghingowa na intindihon an mga leksyon kan saindang mga maestro sagkod maestra.

Mayo ini sa saindang magurang, mayo sa maestra. Pwedeng makanood an siisay man sainda kawasa pipilion gugustuhon gigibohon ninda ini.

Si kadakuldakul na oportunidad kuta na nindang mabisto an mga kaklase o kagurubay, o maintindihan an pagkatawo sagkod pagkanood kan saindang mga maestro sagkod maestra—na iyo man sana nanggad an matatada mawawalat maroromdoman pag-agi kan panahon—an mga ini dai na ninda makukua.

Dawa idtong haralìpot na panahon o pagkakataon na iyo an mabilog kan saindang mga alaala kan saindang elementarya, sekondarya—dai na mangyayari.

Máyò na.

Idtong darakupan daralaganan sa may pahurusan o sa likod kan daan nang Marcos Type—o si arambagan rulutuan karakanan sa Home Economics kan Gabaldon Building.

O idtong pagkahiling pagkatagalpo paglikaw sa hinahangaan na kaklase na uto’doy—uminagi sa Wooden Building?

Si hirilingan surubahan hurulnakan sa Hernandez Hall; si koropyahan hiringhingan purusngakan sa O’Brien Library?

Ano an saindang babalikan bubuweltahan maroromdoman pag sinda na gururang?

#BikolBeautiful

Saturday, April 23, 2022

THEN AND NOW, YOU

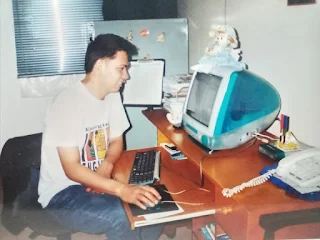

A Gen Xer, you feel fortunate to have witnessed the evolution of digital media all these years.

In the 1990s, you began learning how to operate a computer and begin typing into the green screens using WordStar, WordPerfect, and Fox Database.

You used large floppy diskettes to input—encode—process and print your thesis using the Dot Matrix printer in your school paper’s office.

In the 2000s, you began e-mailing your friends and families a lot and watching trailers and movies on YouTube until the wee hours. You also began blogging, finding so much fun in embedding images and photos onto your essays and blogs that you published on multiply.com or blogger.com.

In the 2010s, you sent videos, too, via your e-mails and shared news, photos, and videos with your friends on social media. You also looked forward to how the videos would stream into your news feed on Facebook and Twitter accounts.

You also joined LinkedIn, Instagram, and Vimeo, among many others, now being so overwhelmed by so much information just using your handheld gadget. You also joined and maintained accounts on Goodreads and Tumblr. For you, the sleek layout of photos and Tumblr was indispensable.

In the 1990s, you went to computer laboratories to encode your academic projects—and the dreaded senior thesis in your university. In the 2000s, you needed to contact your internet service provider so they could fix your company’s troublesome internet modem.

And in the 2010s, you would have to be hooked on a good Wi-Fi if you were to video-stream and witness Pope Francis’s visit to the Philippines outside the country’s capital of Manila in real-time.

All these multi-modal conveniences, through the years, have reinforced any information that you consumed. They have leveled up your interaction and you have become a more learned person owing to these affordances—but most importantly, they have also allowed you to produce knowledge that you can now share with the rest of the world.

#DigitalEvolution

#GenerationXer

#ThenAndNow

Wednesday, April 06, 2022

Anthems of Our Youth, Now Rare

Recently I found that Spotify has the album “Dreams” by Fra Lippo Lippi, which came out in 1992—thirty years ago.

FLL is

that Norwegian new wave duo whose songs played on local FM stations were just

easy to listen to.

At the time, we, members of the

graduating class of Ateneo de Naga High School, were all excited about

graduating.

Sometime in March of 1992, in spending

the last days of our high school, having our clearances signed by our teachers

and the offices where we spent four wonderful years of learning, waiting for

awards announcements, or having our autographs signed by each other in our

classic long manila folders, I remember how we also sang to “Stitches and

Burns”.

The “Dreams” album provided such

unforgettable anthems of our youth—“Stitches and Burns” and “Thief in

Paradise”, among others. It was a hit in those days—enjoying ample airplay on

the local FM stations, that we just found ourselves singing:

“Now I don't want to see you

anymore/ Don't wanna be the one to play your game/ Not even if you smile your

sweetest smile/ Not even if you beg me, darling, please.”—as if we knew them

for a long time.

When my classmate Gerry Brizuela

bought a copy and brought it to class, many of us wanted to borrow it.

Eventually, I was lent the copy and listened to my heart’s content on my

brother’s cassette player.

While “Stitches and Burns” and

“Thief and Paradise” were the easy favorites because they were the ones first

played over the radio and shown on MTV, and probably because of their upbeat

tunes, I got to like “One World”, and particularly “Dreams,” the titular

single, which is one of the many tearful cuts in this rather dolorous album.

Some years earlier—beginning school

in 1988, I grew up listening to FLL’s early hits like “Light and Shade” and

“Angel” being played from our cousin Glen’s room next to ours.

I grew up listening to and

eventually mouthing the lyrics of “Every time I See You”, “Shouldn’t Have to Be

Like That,” or “Some People”, among others—while reviewing for the Algebra exam

of Mr. Rey Joy Bajo or reading the Gospel Komiks for Miss Cedo’s Religion class

or making the Social Studies project under Mrs. Luz Vibar.

But during my senior year in high

school, the songs in Fra Lippo Lippi’s “Dreams” album sounded different but I

liked them all so much.

I wonder why I felt so good

listening to these songs. I wonder why my heart seems to sing, too, when the

songs of any singer all seem to be crying. Why have I, all this time, always

taken delight in these lyrics: “How many rivers to cross—/ Tell me how many

times must we count the loss/ Did you see the face of the broken man, head in

his hands?”

Why have such sad songs thrilled me

so much—that I cannot get enough of them; or that I would rather choose to

listen to them than the others: “Open your eyes to the world/ Light the light

for the ones who are left behind/ Love is in need of a helping hand/ Show us

the way?”

“Once in a while, you feel like

you’re on your own/ And nothing can keep you from taking a fall/ Like there’s

no way out/ Hold on to your dream...”

“It’s all I’m thinking of/ It’s all

that I dream about/ It’s right here with you and me/ and still it's so hard to

see/ still finding my way... still finding my way…my way.”

#FraLippoLippi

#HighSchool

#HardToFind

#NewWave

#Rare

Tuesday, March 15, 2022

Madonna of the Chair

CALAUAG, NAGA CITY—Of all the photos taken at my cousin Maita Cristina’s daughter’s birthday celebration last night, this one makes me take a second look. The way my cousin holds Celestine Faith in her arms reminds me of Raphael’s Madonna of the Chair which I first saw in my Grade 6 class in the late 1980s, which I have not forgotten since.

An iconic High Italian Renaissance art from the 1500s, Raphael’s masterpiece portrays the Blessed Virgin cuddling a cherub-like baby Jesus, as his cousin John, son of Elizabeth, watches adoringly.

Sunday, November 28, 2021

‘Don’t English Me, I’m Panic’

Iníng mga nagpaparapansúpog o nan-iinsúlto sa mga tarataong mag-irEnglish—na ngonyan inaapod sa social mediang “English shaming”, “smart-shaming”, o kabáli na sa mas dakúlang terminong ‘anti-intellectualism’—daí man daw sinda an enot na pinasurúpog kan mga aki pas'na?

Tibaad kadto, sinda nag-iskusar man na mag-inEnglish sa klase ninda sa elementarya o dawà gayod sa sekondarya. Alagad kawásà si maestro o si maestra—in vez na si potential na makanuod nin tamà—mas nahíling, pigparatuyaw dangan pigparadudúan si mga salà ninda. Kayà nagin self-fulfilling prophecy logod ini sa mga buhay ninda. Dai na sinda naka-“move on” sa trauma.

Kayà pag-agi kan panahon, poon kadto pag-abot sa high school, college asta ngonyan na gurúrang na sa trabaho ninda—sa pabrika magin sa opisina— “sourgraping” na s’na an gibo ninda.

Kawásà dai matukdol kan layas na ayam si nagkakaralay alagad haralangkawon na úbas, sinabi na saná kaining maaalsóm sinda. Kawásà súboót dai niya na maipadágos o mapaáyo an kakayahán sa English—dawa ngáni pwede niya man pag-adalán saná ini—sinasabi niya na sana sa katrabahong Inglesero o Inglesera, “Uy, spokening dollar’!”

“Ano na 'yan—haypalúting ka baga!”

Nakanood ka sanang mag-English, very another ka na.

Abaana.

Mayo man naginibo idtong balisngág na English policy sa klase kaidtong mga 1980s—ásta ngonyan igwá pa—na mabáyad ka sa class treasurer kun mádakop daáng nagtatarám nin Bikol sa laog kan classroom.

Kun mádangog na dai nag-Eenglish, matao nin fine; kun dai man madakop, marhay sana. Kayà si iba ta nganing dai magbáyad, nagparáhiringhingan na s’na. Dai pigparápadángog si totóong dílà ninda. Ginibong aswang si sadiring tataramon ninda. Tiniklop sa cartolina. Iniripit, Alagad nag-uruldot si iba. Itinágo sa paldá. Linuom. Nagmayòmò. Pagsangáw, maparàton na. Si English, iyo na ngonyan si kontrabida.

Kan sinisingil na kan tesorerang si Malyn si Pablo ta mga dies pesos na daá an babayádan niya, simbág saiya kan taga-Bigáas na matibáyon magbasábas, “Recess baga ko ka’to nagtarám—hay’paluting ka! Dai mo daw ‘ko. Don't me!”

Thursday, November 25, 2021

Knowledge Production before the Age of Internet

In the 1990s, I attended high school and college classes where we would be periodically asked to “research” on some of the topics covered in the syllabi. This was before the age of Google and Wikipedia.

Based on project-based learning, our subjects covered topics that would now and then require us to research from knowledge coming from the local community—interviews with the local people and yes, folk wisdom and social history.

In other words, not all the things we tackled in class come from the top-down knowledge flow led by the teacher. This was because these teachers—primarily those in the social sciences—did not rely on the textbook. In more senses, I have been a participant and witness to the rather lateral knowledge flow in the classroom.

When classmates reported on legends culled from the local folks; or when we submitted interviews with overseas Filipino workers on economic diaspora; or when we asked our parents to become parts of answering questions related to family, we were being active components of the knowledge production.

Once in our junior high school Practical Arts class which covered “Retail Merchandising”, I was asked to profile our local electric cooperative two rides away from our school campus. So I spent several afternoons rummaging through their archives and learning the dynamics of power distribution, and losses owing to jumpers and all other forms of pilferage, etc.

I was fortunate to learn about the power supply in the process. It was participatory learning galore.

For that project alone, I could say, I was not only assessed by my teacher but also appraised for efforts that rendered my output originality and authenticity inasmuch as it had come from the invaluable knowledge supplied by our local community.

Wednesday, November 10, 2021

Writing: Then and Now

Back then, I would crumple papers to rewrite my letters from the very beginning because of my erasures—I wanted them to be neatly written. I also once tried typing my letters and signed them with my name in the end but it was laborious.

But using the keyboard or keypad now, I am amazed how I can articulate my expression with precision. I can delete wrong words if I need to or just want to. I can also compose my sentences more neatly than before because of the “Delete” function of any computer or mobile phone.

Any gadget’s “Delete” function has gotten rid of the scratch papers I would have otherwise needed so I could rewrite my words and sentences and finish a clearer letter or article.

When I thought of changing a word I just wrote, I crossed them out—but since I knew I didn’t have the luxury of paper, I would first carefully think of the right word to use before I wrote them.

Meanwhile, the word processing machine—I mean, the computer—has given me more options. With it, I could now write more freely—or more aptly, faster—I can now type whatever comes to mind because I know that I can delete and edit these words anytime later if I need to.

When I began using computers in writing, I was also amazed how my spelling can be corrected by the machine. The Spell-check feature of the computer informed me of more words than I knew. I also became aware of which better words to use using the Shift F7 or to get alternative words I can use for what I wrote. I used to do previously by referring to a thesaurus.

The formatting feature of these gadgets also adds to the clarity—and beauty—of my expression. As an image, for example, a carefully chosen font can add to the tone of my message.

I have also been blogging since the 2000s. In blogging a post, from then until now, I have posted my articles, but also have them rewritten later.

Sometimes, when someone reacts to my post on social media, they virtually become my “reviewers” if not co-authors—pointing out a typographical error in one or correcting my words or facts in another. When this happens, I promptly correct such and other errors so that my writing would be clearer and better to them. I even revise the piece altogether based on any comments of the readers online.

Furthermore, the “Edit” feature online does not only help me correct a written blog—it also allows me to add more ideas that enriches the original article.

In sum, the more open writing space afforded by the social media and internet allows my ideas to be expressed freely—with the added incentive of being corrected and even enriched by those who read my articles.

Finally now, in posting this article, the Grammarly app installed as extension on my browser suggested to me the tone of my own article, saying that it sounds not only formal and confident but also optimistic.

It also asked me whether these said adjectives are just right; and I just clicked on the three checks to agree!

Saturday, October 30, 2021

Privileges of Learning

In high school, I probably did the same thing because of the rules we had to follow but I enjoyed it especially how our teachers made us engage with lessons.

Within the halls of Ateneo, my

senior year in high school was particularly memorable. Toward the end of the

year, we were required by our English teacher to dig deep into the life of one

prominent person in history from A to Z. Assigned to the letter “F”, I made a

shortlist which included Michael Faraday, Robert Frost and Sigmund Freud.

Eventually, I chose Freud.

Within the halls of Ateneo, my

senior year in high school was particularly memorable. Toward the end of the

year, we were required by our English teacher to dig deep into the life of one

prominent person in history from A to Z. Assigned to the letter “F”, I made a

shortlist which included Michael Faraday, Robert Frost and Sigmund Freud.

Eventually, I chose Freud.

Up until the 1990s, I had to browse books and scour card catalogs from the library to make that paper. These were no days of Wikipedia—my classmates and I had to source out the lives of these famous people from tomes of books in Amelita’s Verroza’s kingdom called Periodicals Section of the old high school library on the ground floor of the Burns Hall.

Some of us even had to invade Ms. Esper Poloyapoy’s and Aida Levasty’s College Circulation across the hall in the Burns Hall. There in the College Library was where I found the juicier Freud—in the definitive biography by his bosom friend, Ernest Jones. Encyclopedia Britannica, World Book, Encyclopedia Americana, all encyclopedias and primary sources—these were the heyday of index cards filed in that brown box—title, author and subject cards. I did not know why but why of all these cards, it’s the subject card that looked the most beautiful of them all. And from that class, some fifty personalities were featured enough to collect in a compendium of sorts. That project I think was legendary.

After our high school graduation,

my classmates went to enroll in universities while I stayed in the same school.

At the time, studying in a bigger school in

For any youth at the time, there was nothing cooler than that. It did not only mean pursuing courses that suited your taste; it also promised an idyllic academic environment we’d see in the university brochures. It probably also meant “more knowledge”—even as these universities would place prominently in the world rankings, and so on. So did it mean having better chances to succeed in life? Yes.

In college, meanwhile, some of my course papers and essays were more directed to answering key questions to satisfy their rubrics. But certainly, other outputs in the humanities and social sciences were born of my own insight and creativity. Were the didactic and the authentic approaches prominent in my college education? Probably.

Nevertheless, all knowledge that I could have known only lay everywhere—from the books and encyclopedias to almanacs to journals—but were they accessible to me? No. Did our school library have a big collection of these? Not really.

So this was the time when one had

to go to a university to access a piece of information which was only available

from the exclusive collection of this school or that university. Knowledge

before the age of the internet was so precious and rare—one had to search it as

if on a mission, as it were.

So this was the time when one had

to go to a university to access a piece of information which was only available

from the exclusive collection of this school or that university. Knowledge

before the age of the internet was so precious and rare—one had to search it as

if on a mission, as it were.

But when every school had interconnectivity, things changed. Schools in the regions now “mattered”. They became equally competitive—along with the leveling up of the graduate-level faculty who now came back to their departments.

I was surprised that I could now find books easier through an online public access catalog or OPAC in our school. If then, I relied too heavily on what my teachers had to say, this time, much knowledge and information were efficiently at my disposal.

Everything that I only probably wondered about because I heard them from my teachers or was sparked by their discussions I could now probably know elsewhere. I have been so enamored by so much information I can now find online. And since then, I have not stopped.

Years ago, I had to spend hours in

the library to come up with my project, I had to compare notes with my

classmates on their own and I had to see my teachers in the Faculty Room

personally to submit to her the required journal, now, everything is different.

Years ago, I had to spend hours in

the library to come up with my project, I had to compare notes with my

classmates on their own and I had to see my teachers in the Faculty Room

personally to submit to her the required journal, now, everything is different.

-

Reading Two Women Authors from Antique Mid-May 2006, the University of San Agustin ’s Coordinating Centerfor Research and Publicatio...

-

Rating: ★★ Category: Movies Genre: Horror Erich Gonzales, Derek Ramsay, Mark Gil, Epi Quizon, Maria Isabel Lopez, Tetchie Agbayani Directed ...

Songs of Ourselves

If music is wine for the soul, I suppose I have had my satisfying share of this liquor of life, one that has sustained me all these years. A...